|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Funct. Plant Biol. 35: 1123-1134.

|

|

|

|

Cahill, J.F., J.P. Catelli, and B.B. Casper. 2002. Separate effects

of human visitation and touch on plant growth and her-bivory in an old-field community. Amer. J. Bot. 89: 14011409.

|

|

|

|

Cahill, J.F., S.W. Kembel, and D.J. Gustafson. 2005. Differential

genetic influences on competitive effect and response in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Ecol. 93: 958-967.

|

|

|

|

Carpenter, C.D. and A.E. Simon. 1999. Preparation of RNA. In J. Martinez-Zapater and J. Salinas (eds.), Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 82. Arabidopsis Protocols. Humana Press Inc, pp. 85-89.

|

|

|

|

Cehab, E.W., E. Eich, and J. Braam. 2009. Thigmomorphogen-esis: a complex plant response to mechano-stimulation. J.

Exp. Bot. 60: 43-56.

|

|

|

|

Clements, F.E., J.E. Weaver, and H.C. Hanson. 1929. Plant competition: an analysis of community functions Carnegie Institution, Washington DC, USA.

|

|

|

|

Connolly, J. and P. Wayne. 1996. Asymmetric competition between plant species. Oecologia 108: 311-320.

|

|

|

|

Craine, J.M. 2005. Reconciling plant strategy theories of Grime

and Tilman. J. Ecol. 93: 1041-1052.

|

|

|

|

Craine, J.M. 2009. Resource Strategies of Wild Plants. Princeton University Press.

|

|

|

|

De Hoon, M.J.L., S. Imoto, J. Nolan, and S. Miyano. 2004. Open source clustering software. Bioinform. 20: 1453-1454.

|

|

|

|

Eisen, M.B., P.T. Spellman, P.O. Brown, and D. Botstein. 1998.

Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression

patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8: 14863-14868.

|

|

|

|

Falik, O., P. Reides, M. Gersani, and A. Novoplansky. 2003. Self/non-self discrimination in roots. J. Ecol. 91: 525-531.

|

|

|

|

Gibson, D.J. 2002. Methods in Comparative Plant Population Ecology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

|

|

|

|

Gibson, D.J., J. Connolly, D.C. Hartnett, and J.D. Weidenham-mer. 1999. Designs for greenhouse studies of interactions between plants. J. Ecol. 87: 1-16.

|

|

|

|

Goldberg, D.E. and D.E. Barton. 1992. Patterns and consequences of interspecific competition in natural communities: a review of field experiments with plants. Amer. Nat. 139: 771801.

|

|

|

|

Goldberg, D.E. and K. Landa. 1991. Competitive effect and response: hierarchies and correlated traits in the early stages

of competition. J. Ecol. 79: 1013-1030.

|

|

|

|

Grace, J.B. and D. Tilman (eds.). 1990. Perspectives on Plant Competition. San Diego: Academic Press.

|

|

|

|

Grime, J.P. 1979. Plant Strategies and Vegetation Processes. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

|

|

|

|

Keddy, P.A. 2001. Competition (2nd Edition). Dordrecht: Klu-wer Academic Publishers.

|

|

|

|

Kilian, J., D. Whitehad, J. Horak, D. Wanke, S. Weinl, O. Batis-

tic, C. D'Angelo, E. Bornberg-Baur, J. Kudla, and K. Har-ter. 2007. The AtGenExpress global stress expression data set: protocols, evaluation and model data analysis of UV-B

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

light, drought and cold stress responses. Plant J. 50: 347363.

|

|

|

|

Leakey, A.D.B., E.A. Ainsworth, S.M. Bernard, R.J. Cody Markelz, D.R. Ort, S.A. Placella, A. Rogers, M.D. Smith, E.A. Sudderth, D. J. Weston, S.D. Wullschleger, and S. Yuan. 2009. Gene Expression profiling: Opening the black box of plant ecosystem responses to global change. Global Change Biol. 15: 1201-1213.

|

|

|

|

Littell, R.C., G.A. Milliken, W.W. Stoup, R.D. Wolfinger, and O.

Schabenberger. 2006. SAS for Mixed Models, 2nd edition. SAS Institute, Cary, NC.

|

|

|

|

Michaels, S.D. and R.M. Amasino. 1999. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 11: 949-956

|

|

|

|

Mutic, J.J. and J.B. Wolf. 2007. Indirect genetic effects from ecological interactions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol.

12: 2371-2381.

|

|

|

|

O'Brien, E. and J.H. Brown. 2009. Games roots play: effects of soil volume and nutrients. J. Ecol. 96: 438-446.

|

|

|

|

Ohto, M., K. Onai, Y. Furukawa, E. Aoki, T. Araki, and K. Naka-mura. 2001. Effects of sugar on vegetative development and floral transition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 127: 252261.

|

|

|

|

Peng, M., C. Hannam, H. Gu, Y.-M. Bi, and S.J. Rothstein. 2007. A mutation in NLA, which encodes a RING-type ubiquitin ligase, disrupts the adaptability of Arabidopsis to nitrogen

limitation. Plant J. 50: 320-337.

|

|

|

|

Peng, M., D. Hudson, A. Schofield, R. Tsao, R. Yang, H. Gu,

Y.-M. Bi, and S.J. Rothstein. 2008. Adaptation of Arabidop-

sis to nitrogen limitation involves induction of anthocyanin synthesis which is controlled by the NLA gene. J. Expt. Bot.

59: 2933-2944.

|

|

|

|

Purves, D.W. and R. Law. 2002. Experimental derivation of functions relating growth of Arabidopsis thaliana to neighbour size and distance. J. Ecol. 90: 882-894.

|

|

|

|

Putterill, J., F. Robson, K. Lee, R. Simon, and G. Coupland.

1995. The CONSTANS gene of Arabidopsis promotes

flowering and encodes a protein showing similarities to zinc finger transcription factors. Cell 80: 847-857

|

|

|

|

Saeed, A.I., V. Sharov, J. White, J. Li, W. Liang, N. Bhagabati,

J. Braisted, M. Klapa, T. Currier, M. Thiagarajan, A. Sturn, M. Snuffin, A. Rezantsev, D. Popov, A. Ryltsov, E. Kostuk-ovich, I. Borisovsky, Z. Liu, A. Vinsavich, V. Trush, and J. Quackenbush. 2003. TM4: A free, open source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques

34: 374-378.

|

|

|

|

SAS Institute Inc. 2002-2003. The SAS system for Windows, Ver 9.1. SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA.

|

|

|

|

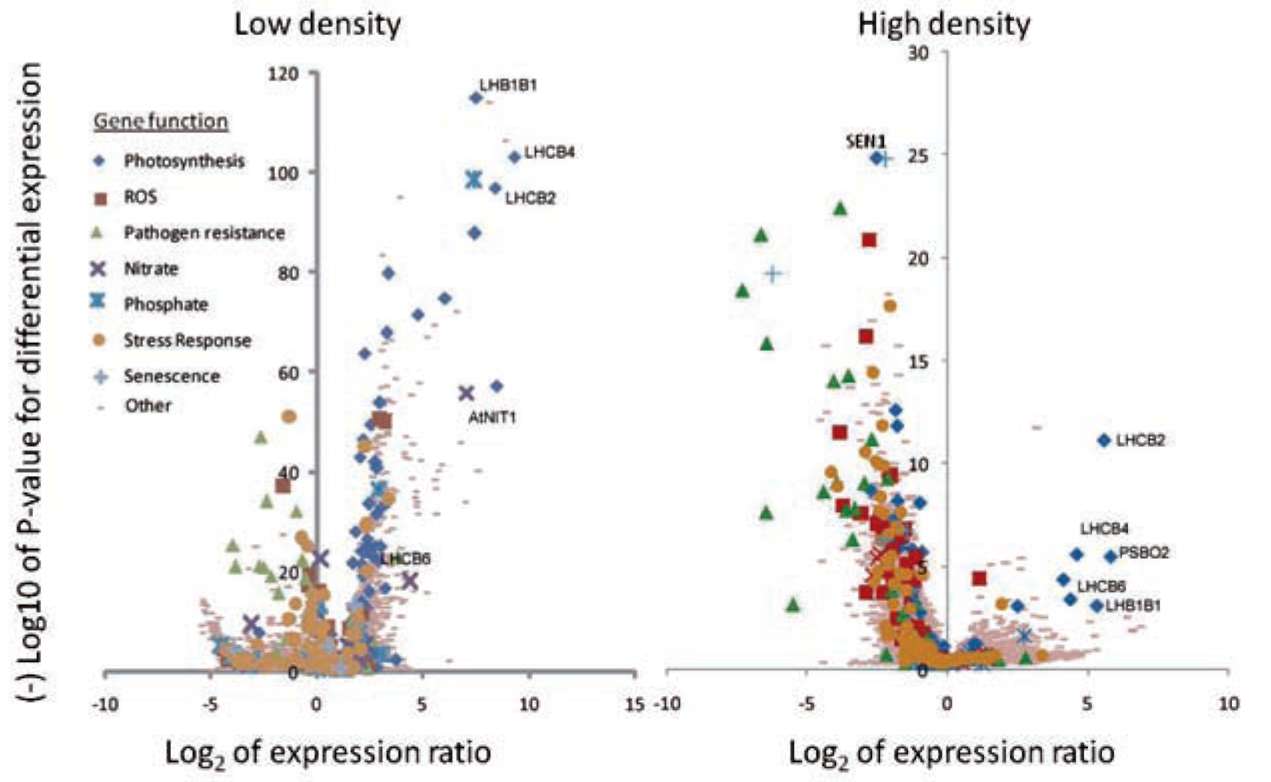

Schenk, P.M., K. Kazan, A.G. Rusu, J.M. Manners, and D.J. Maclean. 2005. The SEN1 gene of Arabidopsis is regulated by signals that link plant defence responses and senescence.

Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43: 997-1005.

|

|

|

|

Schmidt, S. and J.T. Baldwin. 2009. Down-regulation of sys-temin after herbivory is associated with increased root

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|